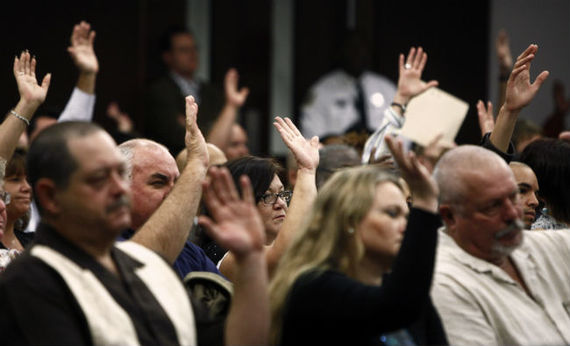

Americans who did not show up for jury duty as mandated raise their hands in response to a question from Circuit Judge Gregory Holder, at a lecture on civic responsibility in Tampa, Florida on November 4, 2011. (Skip O' Rourke/AP)

How can one appreciate an obligation? This is a question approximately 30 million Americans don't ask every year when they receive their jury summons because they are too busy grumbling about this core constitutional responsibility of citizenship. This is also a question of growing importance as courts are struggling to find enough jurors for trials.

It all begins with a letter in the mail. "Dear Citizen," it reads. You hold in your hand an invitation. Sure, it uses the word "summons," and is probably not the kind of invitation you look forward to receiving. Yet, it is still an invitation -- an invitation to participate in the American experiment of self-government. And you can feel flattered that you have been invited. It means that you have not committed a felony (that anyone knows about), that you are mature enough to judge others, and that your community needs you. It's only polite to accept. And, it's even better to think about how you might enjoy the experience.

Turning the dread of jury duty into a form of enjoyment begins with understanding why jury duty matters. Simply put, it may well be the closest you ever come to the Constitution -- not just exercising a right it gives you, but participating in the process through which constitutional rights and values come alive in practice. In a country formed from a single founding document, it is amazing how disconnected most of us are from its meaning and purpose. Jury duty changes that reality - it is a day of constitutional connection. It is also a government-provided free pass from your normal family and work responsibilities. It is the law of the land that you cannot complete your workaday routine. Jury duty thus provides an opportunity (with plenty of waiting time) to reflect on our shared constitutional values.

What are these constitutional values? Participation, deliberation, fairness, equality, accountability, liberty, and the common good - these are constitutional values, and they are embedded in jury service.

A jury summons is an invitation to participation. Jurors are asked to involve themselves in some of the most personal, sensational, and terrifying events in a community. It is real life, usually real tragedy, played out in court. Jurors confront disturbing facts, bloody images, or heart-wrenching testimony. A jury may have to decide whether a man lives or dies, or whether a multimillion-dollar company goes bankrupt. A jury will have to pass judgment in a way that will have real-world effects on both parties before the court. This active role was not accidental. Participation in jury service teaches the skills required for democratic self-government. Being a juror lets you develop the habits and skills of citizenship.

What are these "democracy" skills? Think about what is required for a politically active nation. As a juror, you are asked to "vote" based on contested facts. You must debate issues framed by contesting parties. This involves listening to others and tolerating dissenting views (as well as expressing your own opinions). Jurors necessarily expand their social interaction with different types of people, broadening perspectives, contacts, and sources of information. To apply the law jurors must understand the law, the rights of the parties, and the legal rules guiding the decision. Each of these participatory skills--deliberation, debate, tolerance, cooperation, civility, legal decision making--is what we need for a democracy to work. The participatory aspect of jury duty shapes our constitutional character. Those habits and skills, our civic education, helps define who we are as Americans.

Or, as another example, take the value of deliberation. In the very first sentence of The Federalist Papers, a collection of essays and arguments in favor of the U.S. Constitution, Alexander Hamilton invited Americans to this different way of deciding, "You are called upon to deliberate on a new Constitution," he wrote (emphasis added). It was a call that perfectly fits the thinking of a democracy. Deliberation involves collective decision making--a willingness to think together using reason and informed discussion to come to a final decision.

Why is deliberation important? Because the process of deliberating--of sitting down and hashing out a problem with others--creates better thinkers and better decisions. As thinkers you become invested, informed, and connected. Such dynamic thinking forces you to consider different ideas and reason your way to a final decision. Through the process of deliberation, jurors are made aware of different viewpoints, sometimes even new worlds, as they are asked to judge life choices, industries, and realities that they may never have encountered before. Through jury instructions, jurors necessarily inform themselves about the legal system and the legal rules at play. Throughout the trial process, jurors develop the social mores necessary for success in other group activities. After all, if you can work with twelve people to agree on a verdict, you might be able to work together in a democracy.

Or as a final example, take the principle of equality. Throughout your jury service, you are known by a number--a juror number. You respond to that number. There are no nicknames or familiarities on jury duty. In the same way there are no titles. Whether you are a soccer mom or a Senator (or both), you are simply a number to the jury system. The number is not meant to insult, but to equalize. It provides the anonymity of being a citizen, one of millions who are doing exactly what you are doing in court: waiting for his or her number to be called.

Jury service allows you to see equality in action. In a world that is anything but equal, we tend to forget what equality feels like. You know your presidential vote counts as much as anyone else's, but you also know that the lobbyists, interest groups, and activists have more influence in the political process than your single vote. But in the jury room those differences become irrelevant. Whether you are a rocket scientist or rock guitarist, a linguist or laborer, jurors are given the same facts. Jurors see the same witnesses, hear the same arguments, and get an equal voice in the decision. Thus, the principle of one person, one vote, is actually observable on jury duty. This leveling mechanism strips away the divisions of our normal, unequal society. For a brief moment you see how democracy is supposed to work.

The invitation to jury service is thus an invitation to understand our most basic national principles. The simple fact is that jury duty is one of the few constitutional rights that every citizen has the opportunity to experience. It remains an American bond. It connects people across class, national origin, religion, and race. Jury experience exists as one of the remaining connecting threads in a wonderfully diverse United States. It links us to our founding principles and challenges us to live up to them. Every time you serve as a juror, you become closer to this constitutional spirit; and every time you reflect on and appreciate these principles, you strengthen our constitutional character. That is the joy of jury duty.